After considerable delay I can finally provide a summary of the events of the Empire Campaign covering the years 300 BC to 291 BC. Again the campaign has provided some interesting context to a range of battles with some upsets along the way.

In 299 BC Ptolemy, now some 68 years old, determined to launch yet another offensive into Cyrenaica under his own command and subdue it. Too many previous attempts under his generals had after all failed. Unfortunately little is known of the desperate battle that was fought near the coast on a relatively open plain. Indications are that victory hung in the balance for some time as the armies pressed each other seeking advantage. However, Ptolemy finally defeated his enemy and with the ensuing slaughter Cyrenaica was finally absorbed into Ptolemy’s kingdom.

Even more dramatic clashes were unfolding in the west. Having secured their position in Sicilia, Carthaginian forces in 298 BC invaded Magna Graecia. An alliance of several Italiot Greek cities allowed the assembly of a significant army with which the Carthaginians could be defeated. In the Summer of 296 BC battle was joined. The Italiot Greeks formed up with their right somewhat anchored by the hill town of Quiesa with their army stretching to the left across an open plain. Concerned that the Carthaginian fleet would land troops a proportion of the army was held in reserve while other hoplites defended the city walls. Despite this the Italiot Greeks had a greater number of hoplites that outnumbered the Punic heavy foot. Recent rains caused some areas of farmland to be soft, and a hinderence to the heavy foot of both armies on this otherwise open battlefield.

The Carthaginian advance was focussed against the Greek left, which was quickly reinforced. The battle soon drew in the foot of the centre where the Carthaginian forces made significant use of various light troops to screen the advancing African and Libyan hoplites. However, it was on the Carthaginian right that victory was secured as the Carthaginian mounted slowly gained the advantage in a swirling battle. Demoralised by defeat many more cities of Magna Graecia now opened their gates to Carthage.

Despite many cities excepting Punic rule their remained a number of Italiot Greek cities that sought assistance from Rome. Emissaries were dispatched pleading for assistance to which Rome. The Roman Senate, determined to expand its area of influence in the south, dispatched the Consul Marcus Atilius Regulus, at the head of a vast army in 294 BC. The battlefield was open in the centre and Carthaginian right but broken by a steep and rocky hill on the Carthaginian left. The Carthaginians deployed their mounted, a mix of cavalry and chariots, on their right where they considerably outnumbered the Roman mounted.

The Romans struggled to counter the Carthaginian attacks against their left where the combination of chariots and cavalry proved particularly effective. Indeed, the Consul Regulus was almost captured as the Roman left began to collapse. Then Roman resolve in the centre stiffened and the Punic foot suffered a series of almost unbelievable reverses. Unable to withstand the Roman attacks the resolve of the Punic forces collapsed. In the ensuing months much of Punic Magna Graecia was lost as Rome’s influence expanded.

In the east you will recall the previous crushing defeat of Eumenes expedition to India and Seleucus’ seizure of Babylon. These events provided Andragoras, satrap of Bactria, the opportunity to revolt against Seleucus in 299 BC while Seleucus was still attempting to consolidate his position. Respected by Greek and Bactrian, Andragoras quickly secured the province of Bactria and absorbed Greek settlor and native Bactrian into a formidable army. Seleucus determined to crush the revolt and dispatched an expedition under one of his most trusted generals, Antigenes. Antigenes pressed deep into Bactria until in 297 BC Andragoras was forced to face him on a relatively open plain. With such an open field the role of cavalry and light horse would dominate the initial battle with dramatic flank actions. Antigenes gained an advantage but over confidence was dangerous and Andragoras exploited the extended Seleucids, cutting down Antigenes and his bodyguard. With the Seleucid expedition defeated Bactria, at least for now, would remain independent.

Between the east and west Demetrius having tired of a prolonged war with Ptolemy determined a different path and prepared to invade Thracia. Assembling a large army he crossed from Asia in 295 BC and was soon met in battle by Alexander V of Macedonia, son of Cassander. Alexander, short on phalangites, bolstered his army with Thracian auxiliaries before offering battle. The battlefield was dominated by steep and rocky hills as well as woods, yet retained large areas of open ground. Demetrius sought victory and pressed the Macedonian right flank with his mounted, which was countered by Macedonian mounted and a number of Thracians that held the high ground.

Interestingly, neither commander ordering their respective phalangites forward initially, though later, as the battle progressed, each deployed their phalanx in massed ranks opposite each other on open ground. Yet it was the battle on the flank where the battle was decided. Here the combat swung back and forth until finally the Antigonid left comprising the bulk of Demetrius’ mounted, collapsed. Yet, Alexander’s casualties were such his pursuit was limited. However, Thracia remained firmly under control of Macedonia.

Having defeated the Antigonid invasion of Thracia, Alexander V of Macedonian, replaced his casualties and turned his attention to the independent city states of Graecia in 292 BC. While a number of cities opened their gates to Alexander others rallied around an army formed by Sparta and led by Cleonymus. Seizing the initiative Cleonymus marched his army out to offer battle. He deployed his Spartans and his most trusted allies on the left while his less committed allies extended the right.

Alexander advanced his Macedonians onto the open plain and focussed his attack against the Greek right using the bulk of his Thracian mercenaries as well as his xystophoroi under his personal command. Meanwhile his phalangites and elephants pinned the Greek centre and his right was held by his remaining mounted and light troops. While the initial charge of the Macedonian xystophoroi shattered the Greek line many of the Greek allied hoplites reformed and fought with renewed determination.

Cleonymus, aware he must attack the Macedonian centre, or suffer defeat, ordered his remaining hoplites forward. While Spartan hoplites on the Greek left overwhelmed the Macedonian right Greek psiloi engaged the Macedonian elephants. As these pachyderms routed they exposed the Macedonian phalanx which was simultaneously attacked frontally and from the flank. This sudden turn of events demoralised both Alexander and his army, but such are the vagaries of war. As his army collapsed Alexander was forced to retire, his hopes of Greek hedgeomony shattered.

At the end of the decade the various states control the following provinces, the first province being the home province:

- Carthage: Africa, Numidia, Iberia, Sicilia

- Rome: Italia, Magna Graecia

- Macedonia: Macedonia, Thracia

- Antigonids: Asia, Pontus

- Seleucids: Mesopotamia, Persia, Parthia, Armenia

- Ptolemaic: Aegyptus, Syria, Cyrenaica

Independent states currently comprise: Gallia; Cisalpina; Illyria; Graecia & India.

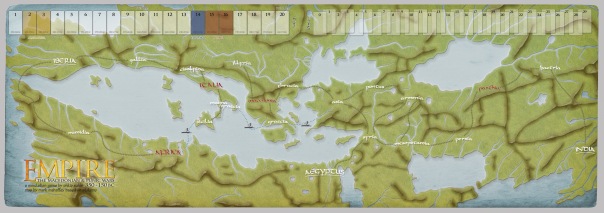

Having now completed three campaign turns, and resolved around eighteen battles, I have spent some time evaluating the campaign mechanics. A couple of issues have become apparent. First is the challenge of organising games where frequently players are unavailable. Secondly, with strategic boundaries constrained by geography many games have involved the same players. I had hoped this would have been countered by other players controlling independent provinces, but it hasn’t significantly. Having read two articles in Slingshot on automated campaigns I intend to move the strategic elements of the campaign to an automated process allowing greater flexibility in using players to fighting actual tabletop battles. I hope this will address both the above issues. In addition I think I can dispense with two provinces, Cyrenaica and Scythia, instead reverting back to the original Empire map.

Which issues of Slingshot did you find these articles in?

I’ve started digging into Berthier and have a blog post coming out next week that will cover my initial setup and thoughts. I’d love to find other tools and see how they work.

There was a short article called “Simple Campaigning – Hellenic Empires” in Issue 309 (November – December 2016). The map here is very similar to portions of the Empire Campaign. I tend to think simple is ideal, which is why the Empire System originally appealed. I won’t use the proposed rules in the article but they provided some inspiration.

More recently there was an article in the current issue (311). This is considerably more complicated and covers a campaign in 10th Century Britain. However, the article reminded me of the article in Issue 309 which previously I hadn’t had time to read.

Nice one, Keith. Would work very well with DBA.

Generally I agree, DBA works very well. I found I had a little tweaking around terrain and invaders as at first players were too defensive in their terrain selections resulting in overly defensive terrain being placed. I think I have mostly resolved this.

The next item on my agenda is tabletop bonus for great commanders, particularly Hannibal & Scipio. Empire places provides significant bonuses for them.